- Home

- Carrianne Leung

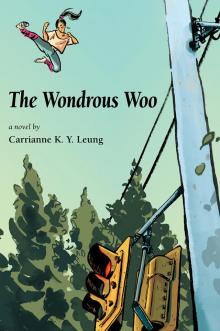

The Wondrous Woo

The Wondrous Woo Read online

The Wondrous Woo

The Wondrous Woo

a novel by

Carrianne K. Y. Leung

INANNA PUBLICATIONS AND EDUCATION INC.

TORONTO, CANADA

Copyright © 2013 Carrianne K. Y. Leung

Except for the use of short passages for review purposes, no part of this book may be reproduced, in part or in whole, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanically, including photocopying, recording, or any information or storage retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Ontario Media Development Organization.

We are also grateful for the support received from an

Anonymous Fund at The Calgary Foundation.

Note from the publisher: Care has been taken to trace the ownership of copyright material used in this book. The author and the publisher welcome any information enabling them to rectify any references or credits in subsequent editions.

Cover artwork: Alexander Barattin

eBook development: WildElement.ca

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Leung, Carrianne K. Y., author

The wondrous Woo / Carrianne K.Y. Leung.

(Inanna poetry and fiction series)

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77133-068-8 (pbk.) — ISBN 978-1-77133-071-8 (pdf)

I. Title. II. Series: Inanna poetry and fiction series

PS8623.E9353W66 2013 C813’.6 C2013-905393-X

C2013-905394-8

Printed and bound in Canada

Inanna Publications and Education Inc.

210 Founders College, York University

4700 Keele Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M3J 1P3

Telephone: (416) 736-5356 Fax: (416) 736-5765

Email: [email protected] Website: www.inanna.ca

To my Pau Pau,

who was the first writer.

Contents

Chapter 1 ~

Chapter 2 ~

Chapter 3 ~

Chapter 4 ~

Chapter 5 ~

Chapter 6 ~

Chapter 7 ~

Chapter 8 ~

Chapter 9 ~

Chapter 10 ~

Chapter 11 ~

Chapter 12 ~

Chapter 13 ~

Chapter 14 ~

Chapter 15 ~

Chapter 16 ~

Chapter 17 ~

Chapter 18 ~

Chapter 19 ~

Chapter 20 ~

Chapter 21 ~

Chapter 22 ~

Chapter 23 ~

Chapter 24 ~

Chapter 25 ~

Chapter 26 ~

Chapter 27 ~

Chapter 28 ~

Chapter 29 ~

Chapter 30 ~

Chapter 31 ~

Chapter 32 ~

Chapter 33 ~

Chapter 34 ~

Chapter 35 ~

Chapter 36 ~

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Chapter 1 ~

Scarborough, 1987

APART FROM KUNG FU FILMS and Chinese New Year, everything our Ba had wanted for us was Canadian. He liked to say he was gung-ho for Canada, gung-ho being a word he used every chance he got. It sounded almost Chinese, he said.

When we first moved to Scarborough from Hong Kong in the late 1970s, Ba had enrolled us in skating classes and skiing lessons, let us eat grilled cheese and renamed us with English names, names with intention, names destined for big things. Sophia’s was after the luscious screen siren Sophia Loren; Darwin’s came from Charles Darwin; and, I got Miramar, which meant “view of the sea” and was the name of a town in Mexico where Ba’s colleague had come from. Initially, my parents had not been able to get the consonants right, saying Mi-La-Ma, but Ba had loved it and laboured for months to pronounce it properly, reading the newspaper aloud at night to practice the “r”s. It was a glamorous name meant for a glamorous person. I wanted to live up to it, for Ba, though the older I got, the more it would be impossible to even try.

Ba had worked hard to instill the great Canadian mythology in the family so we would be as gung-ho as he was. Of course, once we had arrived in our new country, we realized that the mythology was not so great. There had not been any lumberjacks felling trees on our street, or Mounties guiding their horses among the strip malls. But Ba had been undeterred. Once we had settled into our suburban subdivision with its cookie-cutter semi-detached houses and young trees, Ba invited all the neighbours over for a barbeque to make sure we would have some friends right away.

Ma, who had not said much since we had arrived in our adopted country, had set her lips hard and went to work at cooking, making the kitchen come alive to the sound of banging pots and pans. Ma had not been as gung-ho about Ka-La-Dai as Ba. The rest of us had caught on pretty quickly, inserting the “eh” when appropriate and taking up the Canadian accent. Ma never even tried and had kept on speaking in Cantonese to us as much as possible so we would not forget. The language stayed the same, but she was not the same Ma she had been in Hong Kong. She never complained, but she had become quieter. Like all of us, I’d figured she just had to adjust.

But Ba, a wide grin on his face, standing there in his plaid Bermuda shorts, a neon-coloured polo shirt, and his fishing hat on his head as he grilled white fish and slapped the men on the shoulders while they talked, had seemed completely at home.

Standing in our yard, our neighbours had been nervous, we could tell, by the food, by how different we were. They had poked at the pork marinated in red sauce, skewered squid and fish balls, and salad mixed in a whole jar of mayonnaise. They had nodded and smiled and were extremely polite. “Is there plumbing in China? What’s it like to live with communism? Is Hong Kong where all the toys are made?”

We kids had debriefed afterward, examining these gweilos, or foreigners, as if they were lab rats. Some gweilos were hairy, even some of the women. The children were grass-smeared, ketchup-faced, and jumpy as monkeys, but their parents had not seemed to mind. The grown-ups had enjoyed talk about chirpy things: the weather, insecticide for the lawns, their cars. At one point, Ba had mentioned Pierre Trudeau, our hero, but everyone clammed up, so he switched to the weather again and they had all relaxed.

In fairness, they had attempted to accept us; the women invited Ma to their coupon-clipping coffee meetings, and the men gave advice to Ba about eavestroughs. For the kids there had been much more mutual scrutiny. Fortunately, for Sophia, she was born two-finger whistle gorgeous, with long glossy hair and a heart-shaped face, even with her one wayward eye that refused to straighten despite all of Ma’s efforts to train it when she was a baby by moving lollipops back and forth. Sophia had carried herself with the air of her namesake, and the girls gravitated to her with unabashed love. Little Darwin was hyper and loved to run and jump; the boys did not seem to be as particular about who they rode bikes with, so Darwin had fit right in.

As for me, I had never talked much, was thick like the trunk of a tree, and wore glasses that rose up my forehead and halfway down my cheeks. In my secret heart, I had hoped to live up to the breezy whispers of my name by dreaming of ocean panoramas, warm suns, and pretending I was someone else. I had stood off to the side, felt the heavy rim of mayonnaise in my mouth, and watched the scene alone, telling myself I d

id not mind.

Once Ba had found out about Disney World, he believed that pilgrimaging to the epicentre of the American dream would signal to the world that our little immigrant family had finally arrived. When he presented the idea to us, Sophia was in Grade 10, I was in Grade 13, and Darwin, though he looked seven, was deep into being eleven and far more into the violent acts he made his Star Wars action figures commit against each other than twirling around in a boat amid dimpled dolls singing about what a small, small world it was.

But Ba had been oblivious to all of that. When he dumped the brochures out of his cracked leather briefcase onto the kitchen table, he had a smile that took up half his face. Ma had paused at her cooking and wiped her hands on her thighs before peering over his shoulder. “Wah! Florida? They don’t need Florida. What? You think money grows on trees?” Ma had sniffed.

“C’mon, Ma. We’ve never taken them to Disney World, la. They deserve it,” Ba had chided.

“Hrmph,” Ma had turned back to the stove. She was not going to give in that easily.

Sophia and I had stared at the pictures of Snow White in front of her castle. Sophia just flicked her perfect hair behind her shoulder and stuck her nose in the air. I had tried to imagine us at Disney World together. Ma in her giant sun hat, Ba in his sports socks and sandals, the sullen teenage daughters, and the hyperactive son — me the slightly overweight nerd in too-tight Levis; Sophia, the cross-eyed beauty bored out of her blow-dried mind; and, little Darwin dwarfed by his too large second-hand Jedi Knight robes that he only took off to go to school and only after he did after his daily eight-fifteen a.m. tussle with Ma.

“What’s for dinner?” Darwin had come flying into the kitchen, light saber in hand.

“Dar, we’re going to Dis-Nee!” Ba had exclaimed as he tried to wrap his arm around Ma’s waist while she shoved past him to return to her cooking.

“Disney?” Darwin had looked skeptically at the wide-eyed Mickey Mouse brochure. “That’s for babies. Unless Disney made Darth Vader?”

“I don’t think Disney made Star Wars,” Sophia had said in her know-it-all voice. “They’re more into the animals — Dumbo, Bambi. And the princesses. Snow White, Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty.”

“Then forget it. I don’t want to go to some baby place!” He had dropped the photo of Mickey Mouse back on the pile and ran out. “Call me when dinner’s ready, Ma!”

Ba’s smile had fallen like a landslide. “What about you girls? You used to love the princesses.”

He looked like he had been trampled on.

He turned to me, his eldest, his rock, for support. “Miramar? You, too?” he asked quietly.

“Well, yeah, Ba. We’re too old for that stuff.” I had mumbled, resenting that I had to be the one to say it.

“Ah, okay. I made a mistake,” Ba had said tunelessly as he swept the colourful brochures into his bag. “Only that so many of our neighbours have gone with their families. The travel agent said it’s the great Canadian getaway.”

Ma had already turned back to her pots on the stove and was stirring in silence. Ba then clicked his briefcase closed and went upstairs to change. We never talked about it again.

A few months after that, he was dead.

Chapter 2 ~

These fields will be yours one day, the father said. What good were fields, his irreverent children scowled. The girls were more interested in adorning their hair with jewelled combs while the son wanted to join his friends in chasing prized crickets. The father waited, knowing patience was the plight of the wise.

BA AND I USED TO HAVE this Sunday ritual of making the long hike downtown Toronto to the Golden Harvest theatre in Chinatown where we could take in the kung fu triple feature. Ba had a herniated disc from when he was young, so he lived vicariously through the kung fu masters as they exacted revenge on evildoers or those who had transgressed against their families. Ma didn’t like the fighting, she said, and Darwin and Sophia hated all the standing at bus stops and crowded subway cars, so it was always just me and Ba, surrounded in the dark by grannies cracking pumpkin seeds with their teeth and the scents of roast duck and oranges wafting out of Tupperware containers.

Initially, I had gone with Ba just to keep him company, but as we watched the heroes move from happy innocence to tragedy to the final victory, I got hooked. Soon, I could hardly wait through the opening: the jaunty music, the debonair young men, the giggling peasant girls, everyone enjoying a happy-go-lucky life in their close-knit village with fertile fields and clear skies. This part had always seemed stupid to me, artificial. It was just like Scarborough. I would feel the sourness in my stomach when I thought about the gweilo kids at school, the same ones who had come to our summer BBQs and eaten our food, who in the halls, chanted “chinky-chong” taunts just loud enough for us to hear. That one girl who had gone around the cafeteria imitating Ma’s herky-jerky shovelling motions while her fingers squished her eyes into slants.

But then, once the movie got going, I could not help but sit on the edge of my seat. This was when the warlords, the greedy landowners or corrupt government officials stripped the young protagonist of everything — his village, his family, his livelihood. As the sole survivor, he would receive training from the kung fu master, the old sifu, and eventually become the greatest warrior who ever lived, taking his revenge in incredible fight sequences and returning home victorious.

That part had made me feel as if I could leap through the screen with the grace of these heroes and kick some serious ass. When the credits rolled, Ba and I had always applauded.

While all the glory in these films belonged to the men, after a while, I had started noticing the women. They were usually on the periphery: the servant girls, the blind princesses, the poor orphans, the unwilling brides. Sometimes, the beautiful maidens’ function was just to be beautiful, and they often ended up dead. But once in a while, when one of the women swept her long tresses aside and flew through the air, my heart would stop.

At night, I had only needed to close my eyes and I would inhabit their world, their quiet power. I imagined myself porcelain-skinned, clothed in layers of bright silk garments, feigning shyness by hiding behind a fan. The next moment, I yelled a battle cry and pointed to an opponent for offending my dignity. In a complex dance, we locked arms and battled to the death. I was always the victor, winning the awe and respect of the entire village, including the other top kung fu hero, the most handsome man of the bunch, the one whose sweat glistened as it dripped down his brown neck. Together, we travelled tirelessly, hunting the bad guys, avenging the innocent and saving the world.

When I was in Grade 11, we got our first VCR. Ba and I had stopped going to the Golden Harvest because even we had to admit it was far easier to stay home in our sweatpants than to spend all that time going downtown, especially since Ba had to make that commute every day for work anyway. But Sunday afternoons had remained our time; during the week he would pick up armloads of Hong Kong videos from a store on Spadina Avenue, and we would camp out all afternoon. When Sophia had whined that we were cutting into her shows, Ba bought another TV for the basement.

One afternoon by the third movie, I got annoyed. “These women are getting shafted,” I had said, pointing to the eye-batting peasant girl washing clothes in the brook. “If she hadn’t rescued her man from drowning, the show’d be over.”

Ba had leaned over and paused the video, something we never did (we never needed to; peeing could always wait). He had scratched at his chin and looked me in the eye. “One day, Miramar,” he said, “you should write these stories from the side of the women. Make the world know how powerful they are. Like you.”

I had been mortified when my eyes welled up. Ba could always see through me even as I had tried to hide from myself. I had lived my gung-ho Canadian life in a timid shell. I had found shelter in the safety of our house, tucked my dreams inside these movies, and wished I were relevant

while I hid in the shadows of my life. I had liked believing that deep within I was capable of everything I wanted, but at the same time, I had no idea how to be that person.

I thought I still had time to figure it all out. I thought there would be years of Ba in his La-Z-Boy, me on the carpet, our hands balled up in fists during the fight sequences and thundering drumbeats, cheering loudly and high-fiving each other when the hero ultimately triumphed. I had thought Ba would always be around to help me find out who I was supposed to be. I was wrong.

Chapter 3 ~

After the screams subsided, and only the burning houses were left, Ye still crouched in her hiding place behind the rocks. She knew she had to get up and look for survivors, but still she waited, hoping for a sign — divine or otherwise. One by one, they came out of the shadows, their whispers growing louder as they groped for one another.

THE DAY HE DIED, I had just finished my last ever high-school exam and was celebrating being part of the graduating class of 1987 at McDonald’s with my best friend, Nida.

“Yeah, but using tampons means you’re not a virgin anymore,” Nida asserted, using her best authoritative voice. She dipped a french fry gingerly into a pool of ketchup.

“You know jack shit,” I mumbled with my mouth full of quarter pounder and cheese.

“Jack shit? What kind of shit is ‘jack shit’?” Nida waved the red-tipped fry at me. We liked to swear like truck drivers when we were together. It made us feel dangerous.

Though I had used exactly three tampons in my life and not very well, I persevered in my impassioned defense. “You insert it, and you forget about it. Well, you don’t forget about it. You know what I mean. You just don’t have that big brick between your legs all day. You can run around, do things, even go swimming. And who cares if you’re no longer a virgin. That’s good. Then it won’t hurt the first time.”

“Ew. That’s so gross. Anyway, my mother would freak if she saw tampons in the house!” We both cackled at the thought of Mrs. Patel coming across a box of tampons. She would likely bang down the basement steps, slide open the storage closet doors to where her pantheon of Hindu gods resided and spend the rest of the day commiserating with them.

The Wondrous Woo

The Wondrous Woo That Time I Loved You

That Time I Loved You