- Home

- Carrianne Leung

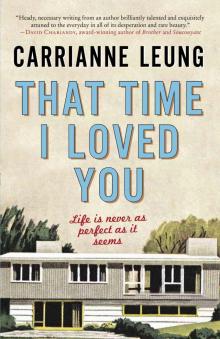

That Time I Loved You

That Time I Loved You Read online

Dedication

To Fenn Archdekin-Leung

I’ll always tell you stories

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Grass

Flowers

Fences

Treasure

Wheels

Kiss

Things

Sweets

Rain

That Time I Loved You

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Grass

1979: This was the year the parents in my neighbourhood began killing themselves. I was eleven years old and in Grade 6. Elsewhere in the world, big things were happening. McDonald’s introduced the Happy Meal, Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Iran and Michael Jackson released his album Off the Wall. But none of that was as significant to me as the suicides.

It started with Mr. Finley, Carolyn Finley’s dad. It was a Saturday afternoon in freezing February. My best friend, Josie, and I were sitting on her bed, playing Barry Manilow’s “Copacabana” over and over again on her cassette player and writing down the lyrics. I was the recorder while Josie pressed play, rewind, and play again a hundred times, repeating the lines over to me until the ribbon finally snapped and we had to repair it with Scotch tape.

“Did you get that, June? Did you get that?” she kept asking me as I nodded and wrote furiously on lined paper. We kept all the transcribed lyrics in a special pink binder marked “SONGS” in my balloon lettering.

I didn’t like the song as much as she did and wanted to switch to “Le Freak” to practise our new dance moves, but Josie was determined to unravel the mystery of Lola at the Copa.

Josie’s brother, Tim, came in the front door, slammed it hard and thumped up the stairs, shouting, “Josie! June! Mr. Finley’s dead. He’s dead! He’s fucking dead!”

At first, I thought Tim was angry at Mr. Finley. We often were mad at him because he was our softball coach and mean. Then I realized by the sound of Tim’s voice that he was serious, that Mr. Finley was dead dead.

Tim burst into Josie’s room to tell us the grizzly details. Mr. Finley had offed himself with one of the hunting rifles he kept in a display case in his basement, beside his collection of taxidermied animal heads. His daughter, Carolyn, was in my class. The one time I had a sleepover at her house, we’d slept in the basement. Dead deer and owl and bear heads had cast eerie shadows on the walls. She’d snuggled into her Benji sleeping bag and drifted off while I was as rigid as the snarling heads above me and didn’t dare close my eyes, fearing that even in their current state they’d go for my jugular. Josie and I had never been invited to a white family’s house before, which is why I had said yes, and after I told Josie all about the horror show, we assumed all white people decorated their homes with dead animal parts. No thank you very much.

Mr. Finley was the first person in the neighbourhood to kill himself. It gave me the chills. Not long after that, Georgie Da Silva’s mother, on a warm June night, shuffled out to their double garage and drank a jar of Javex bleach. At 8:30 a.m., Georgie went looking for her when he didn’t see her in the kitchen. He found her body sprawled on the oil-stained floor, a stream of white sudsy liquid pouring from her nose and mouth, her eyes looking right at him. That’s what all the kids on the street said. We all began to worry: This was my and most of my friends’ first experience of death. It was kind of exciting at first, but then it got scary. Would there be another one? And another after that?

The suicides all happened on what we called the “sister streets.” Our neighbourhood was made up of three streets that ran parallel to one another and were joined by a bigger street running perpendicular. Winifred, Maud and Clara Streets all met on Samuel Avenue. I imagined Winifred, Maud and Clara were sisters from olden times, like in Little Women, my favourite book. Maybe Samuel was their brother, who’d gone off to war. The three sister streets were almost carbon copies of each other, with the same houses—three two-storeys and a bungalow repeated as a pattern—mostly the same cars in the driveways—Fords, Hondas and an occasional Volkswagen—and some form of fruit tree. On my street, Winifred, were crabapples, Maud had cherries and Clara Street’s trees bore plums so sour no one could eat them. These trees were bred to be miniature, so we could never get high enough for a view from their twiggy branches or eat any of the gnatty fruit that fell down and rotted quietly in the grass.

The three sisters streets and their brother, Samuel Avenue, contained my world, all of our homeland operations. All my friends lived here, my school was down the street on Samuel and in the other direction was the way to the plaza with Mac’s Milk, Hunter’s Pizza and Bamboo Garden, which sold takeout Chinese food that my parents said was not real Chinese food. On the other side of the plaza was the “old part” of the neighbourhood, where people had been living longer.

That summer, as they watered their front lawns, the adults leaned across their fences and spoke in hushed voices, flooding their grass with their now forgotten hoses. Us kids gathered in the street with our road hockey gear and baseballs to share whatever intel we’d acquired and trade in gory details. Mr. Finley’s brain was supposedly splattered in a million bits across his basement. My friend Darren said you couldn’t clean brain completely out—that stuff sticks. Darren knew a lot about brains because he was into comic books and his mother was a nurse, so we took whatever he said as fact. As for Mrs. Da Silva, everybody knew she wasn’t right in the head. We often saw her walking around in her housecoat talking and laughing to herself.

Nothing like this had ever happened in our quiet suburban neighbourhood before. No one had even died before Mr. Finley. In downtown Toronto, where the dangerous people lived, at least according to my dad, it probably happened all the time. Dad said downtown was no place for kids because it was dirty and full of fast cars and shady characters, while out here in the suburbs, we were free to play on the street, leave our front doors unlocked and generally not worry about such things. Granted, there was a neighbourhood thief sneaking around, but only small, mostly worthless things were taken—forgotten gardening gloves on the lawn, chipped coffee mugs left on the porch, a rusty screwdriver in a garage. People assumed it was some weird kid’s idea of fun. I had my own opinion on who it was, and it was no kid. But no one listened to me anyway.

My street, like the rest of the subdivision, was brand new. Most of the neighbours had moved in four years ago, right after the houses were finished. My parents loved the neat grid of black road, the bright white stripes to differentiate the lanes, the chain-linked fences that divided our properties but gave us views into the neighbours’ yards, the young, weeping trees lining our streets. They said you couldn’t get “all this” in Hong Kong, where everybody was crammed on top of each other in tiny apartments, and they would sweep their arms to include whatever “all this” referred to, like showcase girls on The Price Is Right. They were always saying, “June, you don’t know how lucky you are that you were born here and not there.” Mom and Dad had come to this country on student visas fifteen years ago, but the way they told it, it was like they were fresh off the boat. But I suppose they had lived in the city for those years in crammed apartments, and moving out here to the suburbs, Mom and Dad finally got some land. Even though it was only a square lawn and a rectangular backyard, this was a big deal. Land was land.

Between the road tar and the pine boards and the wall-to-wall carpeting, the whole place smelled like a new toy just unwrapped. The kids liked to guess what the area had been before they bulldozed it and put up our houses: Farmland, cemetery, someone else’s neighbourhood? But that was for sport. It was brand spanking new and ma

de you feel like anything was possible.

As soon as the houses were built, we all moved in. My parents and I moved from our two-bedroom apartment downtown to our four-bedroom spread of a house in Scarborough. It was only a thirty-minute drive between the two places by highway, but my parents were convinced that the air was even cleaner in the new neighbourhood. At first, it had felt like Disneyland. Since it was the beginning of summer, the heat got us outside, and everybody got to know each other and planned things like fireworks and barbecues on the long weekends. Everybody was invited at first, but then it seemed like people decided who their friends were, and the invitations that used to be shoved in all the mailboxes stopped coming. It was the same for us kids. We met, sized each other up and broke into groups. Things settled into routines.

The suicides changed that. I heard a neighbour say, “But it had all been going so well!” I didn’t know if it was my ears, but he sounded angry, like he’d been let down, as if the local team lost a hockey game even though the captain promised they were going to smash it.

Even though kids from other neighbourhoods went to my school, my very best friends all happened to live on the sister streets. They included the other Chinese families—the Wongs, the Chows, the Changs. Josie was a Chow. My dad said we were Chinese from Hong Kong, not like the Toishan Chinese downtown, who had been here longer and were from villages back in China.

It wasn’t because we were Chinese that we were friends. It just happened that way. There were others who hung out with us, like Nav, who was Indian but “India Indian” and not “Native Indian,” as he would have to explain many times, and Darren, who was Jamaican or Black depending on who was talking. There were also a lot of white kids, but they didn’t play in the streets in packs like we did and tended to go to each other’s houses with tote bags full of Barbies and G.I. Joes. There were some Italian and Portuguese kids and they played in groups. They also mostly kept to themselves and we didn’t play with them very often. We stayed on Winifred while they played on Maud. This arrangement quickly became the way it was. We tried a shared game of volleyball once, stringing a net on one of our sloped driveways. One side was always screaming foul for having to play against gravity, which almost led to the first-ever gang rumble on our street.

Regardless of which group we belonged to—Chinese, white or otherwise—by the second suicide, it felt like we were waiting for something else catastrophic to happen. We were nervous enough to pool our information across the group divides. Like the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew, we started watching our parents carefully, taking note of unusual things. On a Thursday in June, after the school year ended, Cindy Taylor from down at the end of Winifred told us that her father, who put a lot of stock into being well groomed, went to work with a wrinkled white shirt beneath his blue blazer and forgot to shave. Did this mean something? We patted her back, unable to say for sure. Stephanie Papadakis said her mother forgot to put garlic in their moussaka one night, and she never forgot to put garlic in the moussaka. It was easy to jump to conclusions, assume these signs were the beginning of the end. I was a good watcher anyway and observed everything just in case I needed the information for later, but that summer, I made sure to pay extra attention to everything.

My parents were their regular selves. They still worked their same long hours at their office jobs, so I could only watch them before bed and on weekends, and I couldn’t detect a thing. My dad still didn’t talk to me much, same as always, shooing me away while he read the paper or watched the news. My mother told me to stop staring at her because I was making her nervous. She was busy getting papers filled out and seeing the lawyer about sponsoring Poh Poh, my grandmother from Hong Kong, to come live with us. When I finally asked her about the deaths, my mother said, “There’s more than meets the eye.” She liked English sayings. She said they were great conversation starters, and she used them a lot in the staff lunchroom at the office where she worked as a keypunch operator. I knew the suicides got to my parents. The creased lines on their foreheads and the pursed lips that lingered long after my questions made my stomach ache.

Because my parents didn’t get home until close to six p.m., I spent my main observation time with an eye on Liz, Josie’s sixteen-year-old sister, who looked after me while she was parked on the couch watching soap operas or reading Harlequin romances. I’d never met anyone so boring. I thought I might be the one who died from watching her.

After Mr. Finley joined the spirits of the dead animal heads in his basement, Carolyn got sent to her grandparents’ place in the country. We waved goodbye as her grandfather’s wood-panelled Ford station wagon pulled out of her driveway and wound down our long street. We chased it until it turned left onto Samuel, and kept waving long after the car had disappeared. I thought I saw Carolyn crying as she drove away. For a long while, it seemed like their house was empty, even though we knew her mother was still there. A month went by, and it was put up for sale. We wondered if the brains were finally cleaned up or whether someone had painted over them.

Georgie Da Silva took to sitting on a lawn chair in his garage with the doors wide open, and everyone who passed by could see him sitting right by the spot where his mom died. For the first few days, his Italian and Portuguese gang gathered around him, gently punching him in the arm and sitting on the ground at his feet, listening to the radio and smoking quietly. Some brought flowers and laid them on the driveway. But when that ended, it was just Georgie, staring at some spot on the ground for hours each day while we played Frisbee football up the road.

It barely rained that summer, and in the sweet, warm air, we made the hours worth it. We met in the morning, dew still on the grass, to play baseball, ball hockey and that game that was a cross between tag and hide and seek, stopping only for lemonade at someone’s house and baloney sandwiches for lunch, staying out until the first street lamp flickered on. Sometimes we would forget all about the suicides because our games would be so fun, but then a kid would come running up the street with some new observation to report, and we remembered. It was too difficult to play hard and be scared at the same time.

It was around the time of Mrs. Da Silva’s suicide that my dad developed a weird friendship with the white boy Larry Lems, the class bully who lived on Maud. Larry had come to our door one day and asked my dad if he could mow the lawn for him or do some odd jobs. When I heard his voice, I ran upstairs to my room like a scared rabbit. At school, everyone knew to keep their distance. Larry hated all the kids not just in our class but in all of Grade 6. He called us by a variety of names depending on what bothered him about us: Sean was Fatso, Cindy was Fucking Idiot, Damian was Retard, Darren was Nigger, Nav was Faggot, Sena was Motor Mouth, Maria was Wop, my best friend, Josie, was Chink #1, and, because Larry didn’t have much of an imagination or vocabulary, I got Chink #2. He stole our lunches, pushed us over even if we weren’t in his way, and challenged all the boys to fights after school, which he nearly always won except that one time Darren got in a good shot and gave him a bloody nose. Darren confided in me after that he had pretended he was the Thing from the Fantastic Four and this did the trick to give him the extra power to clobber Larry. And besides, Darren said, no one called him a nigger and got away with it. That made him such a hero that for weeks afterward, we gifted him with all the choice items from our lunches, the Peek Freans jam-filled cookies, packs of Bubblicious gum, mini bags of Humpty Dumpty chips. That was how much we hated Larry Lems.

So when he showed up at our house, I was naturally horrified when I heard my dad say “Sure” and offer Larry some jobs to do around our house. He even let Larry use his prized 1974 twenty-one-inch model 7263 Lawn Boy with the two-stroke engine, which he would never let me or my mom even touch because he claimed we would cut ourselves for sure since women couldn’t understand the true power of the machine. It was no secret that the Lawn Boy was my father’s real baby. He had purchased it from Sears the first summer we were in the house. He was pretty lazy about mowing the lawn, but for whatever

reason, he loved his mower. He kept the engine well oiled and the blades as sharp as Ginsu knives. He let Larry use the Lawn Boy to cut the grass and also had him weed the flower beds for three dollars. When I heard that arrangement, I almost passed out. Three dollars? He didn’t deserve three cents.

Our backyard had always been a jungle of neglect. Since my parents had day jobs, I was like the latch-key kids the TV news talked about, and there wasn’t much free time or interest on anybody’s part in tending to the yard. But by late afternoon of that first day Larry worked for us, the yard looked good. The grass was neat, free of the choking dandelions and clover. It was as if the whole backyard heaved a sigh of relief. When my dad went out to talk to Larry, I braced myself for the name-calling. My dad had a lot of nervous ticks; his left eye twitched, and his arms would sporadically shoot into the air while he talked, so he’d elbow himself in the ribs several times during a conversation. All this plus the fact that my dad was a chink added up to choice meat for Larry Lems. But it never came. I peered down at them from my bedroom window. With his arms akimbo, my dad checked Larry’s work, nodding with approval. Larry, swigging the can of Pepsi my dad had given him, was honest-to-God smiling. It occurred to me that I had never seen him smile before.

From that day on, Larry came over every week. I still scrambled away at the first sign of him and tore out to the street to be with my friends. It would take a whole lot more than him cracking a smile for me to believe he had changed. My dad found him odd jobs to do and gave him a dollar or two each time. One Saturday, he even showed Larry how to take the Lawn Boy apart and put it back together again, explaining the function of each part. I watched how Larry paid close attention as my dad squirted oil on the bolts and gently removed the blades. He then taught Larry how to hold the blades at the exact angle they needed to be for the grinder to scrape at the edge. He let Larry hold the blades to try to sharpen them himself. Larry looked like he was in heaven. He looked like a kid and not some axe murderer. My father also seemed to enjoy his time with Larry, giving him his complete attention. I figured it was because Larry was a boy.

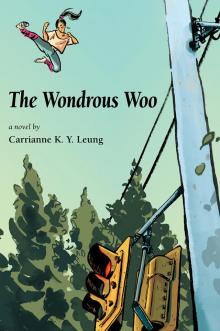

The Wondrous Woo

The Wondrous Woo That Time I Loved You

That Time I Loved You