- Home

- Carrianne Leung

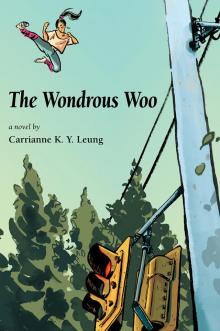

The Wondrous Woo Page 2

The Wondrous Woo Read online

Page 2

It was at this exact moment that I saw my neighbour Stan Knowles running. To be clear, my neighbour Stan was not someone who ran. But here he was, huffing and sweating across the parking lot. We watched him through the large glass window facing Warden Avenue, giggling at his flop of hair, until I saw his eyes and turned cold. He was running for me. I hoped I was wrong, that he was there to see someone else, or he just needed a Big Mac really, really bad, but when we locked eyes, I knew something was horribly wrong and that it was Ba. I didn’t wait for him to get inside; I grabbed my bag and ran out to meet him. I didn’t think about how he had always creeped me out with his jogging suits and sweatbands even though he was, again, not in any way an active person. I tried to ask him questions, but he was too out of breath. We sat in his car in silence the whole way to the hospital.

As soon as I entered the private waiting room where Ma had her head down praying with some of her mah jong friends, I felt the empty space in the air. It was done. I didn’t have to ask. I just had to keep myself from floating away inside the sudden weightlessness of the room.

The police came soon and told me some things. I nodded and spoke to them. I was polite. I helped Ma sign their forms and wished them a nice day. Then they walked away and I left the waiting room. I didn’t go anywhere in particular, just followed the corners of each hall to the next, constructing my own scene of the accident. I started with Ba leaving his office, saying goodbye to everyone then walking toward the subway. He would have passed the travel agency where the Disney World brochures were lined up in the window. He would have boarded his train, his old briefcase by his side and looked up at the ads, probably searching for more Canadian things we could partake in. Then, when his stop arrived, he would have transferred onto his bus. The Scarborough landscape would have passed him by — the wide road, the shopping malls, the early summer weather. It was a gorgeous day, marked by gentle breezes and an impossibly blue sky. Maybe he hummed. Sometimes he did that. A familiar tune that made him feel sentimental. He loved The Platters. In my mind, I made him hum, “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.” He would have got off on his stop at Baymills and Birchmount, and, as he always did, instead of walking the extra hundred metres to the crosswalk, he jaywalked, just to get home those few minutes faster. As he waited on the curb, he probably thought about the word “jaywalk,” probably playing with it as he liked to do with the origin of English words. Did the term “jaywalk” refer to a bird, perhaps a jay? Did jays take shortcuts? Maybe he felt like a bird caught in a stream of prey when he found himself crossing the street on his way home. Maybe he was a warrior, ducking and weaving between four lanes of cars, running and stopping. I imagined he loved how his body still knew how to twist and turn after a whole adult life of nine-to-five cubicle days. In the precarious state between life and death, in that moment, I thought he must have felt wholly free. This was my only explanation because no amount of scolding from Ma could ever stop him from taking that shortcut.

The moment he stepped off the curb, a baby blue ’78 Firebird, emblazoned with red flames, threw him eight feet into the middle of the road. And there, two birds came head-to-fateful-head — a dodgy jay and a bonfire of feathers. Then all was still.

Some hours after all the papers were signed and the hospital staff had said their condolences, we went home. In the days that followed, I moved as if beneath water. Voices came in murmurs. People I knew and didn’t know dropped by food that tasted like ground seashells, even soft Canadian noodle casseroles, even my favourite wok-fried vegetables. The light that seeped through the sheer curtains of the house threw everything into a ghostly grey-blue sheen. We were alone, together but separate, as we floated around the house.

There was a funeral, but it felt like I wasn’t really there. It was more like a movie I was watching from a distance. I knew Ba’s co-workers were there, the neighbours, Ma’s church ladies. Everyone seemed so sad and could barely look at us, as though we were ghosts.

Afterward, Ma went to her room, attended to by a clutch of her mah jong church friends who all came out shaking their heads. No sounds emerged from this room, no crying, no talking, just a cold, jagged silence.

Without school, Sophia, Darwin, and I didn’t know what to do with all the hours. Darwin played Space Invaders on his Atari while Sophia played staticky records on her record player. Sophia liked to play everything either too fast or too slow, which annoyed all of us. Her Flashdance single at 33 and 1/3 speed escaped under our bedroom door and seemed to moan quietly through the house. I re-read my stacks of True Confessions magazines, thumbing through the well-worn pages of cheating spouses, incest survivors, and middle-class kleptomaniac housewives. It calmed me to know there were screwed-up things happening in other houses with closed doors.

Sometimes, we found our friends tapping on the door, kicking at the ground. We knew they had come because their parents had made them. We would spend an hour in awkward conversation, maybe play some games on Darwin’s Atari before they would leave. Soon, they stopped knocking.

Even Nida claimed she had so much to do to prepare for university in London, two hours away. I wanted to scream, “London isn’t Siberia; you can buy deodorant when you get there!” but it wouldn’t have done us any good. In my fake alternate universe, the one where Ba was not dead, I wondered if that other Miramar would be buying up deodorant and reams of paper as she prepared to go away to school too. I had been accepted at Carleton University in Ottawa. Now, I wasn’t even sure if I would go.

After two weeks or so, the casseroles stopped coming, which was a relief because the freezer was full. Ma’s friends only stopped in for quick visits in her bedroom. Silence fell a few degrees harder. On our own, the three of us kept the house clean and still ate our Lucky Charms cereal in the morning. We obeyed the eerie hush that had descended, tiptoeing around Ma and Ba’s closed bedroom door. We raised our voices only occasionally to fight over the TV before the rush of events that brought us to that moment returned and muted us back.

Around this time, I felt the need to hold on to something of Ba’s. One hot, humid day, I took his blue scarf from the hall closet and wrapped it several times around my neck to catch whatever of his warmth it still had in it and hold it there.

Darwin then donned Ba’s fishing hat. It was beige with a tartan ribbon around it and was too big for Darwin’s head, but he didn’t seem to mind constantly pushing it off his face. Sophia chose Ba’s green cardigan, the one that smelt like mothballs, which we all associated with Hong Kong. She rolled up the sleeves three times and it hung on her like a bathrobe. We didn’t talk about our new attire.

In the weeks after Ba’s death, we used up the last of the cheques from Ma’s wallet and I started to worry about the money situation. I scoured the closet and found a fresh book of cheques and Sophia forged Ma’s signature so we could cash them. I assumed there must be enough in the account when the bank teller just shoved the money at me without blinking, but I had to wipe my sweaty palms on my jeans in order to take the cash. I found Ba’s bank book and figured out how to pay the bills that were coming in and balance the account. Judging from my estimation, we only had a month’s worth of money left. After that, I wasn’t sure what we would do.

Chapter 4 ~

The eldest daughter has to shoulder the family. When all the men left to avenge their honour, Fan gathered wood and learned how to make fire.

AT NIGHT, WE SPOKE in whispers, and we talked about “it.” Sophia and I shared a room, but when we found Darwin whimpering under the covers one night alone in his room, we dragged his mattress between our two beds. He had said he was just teary as a result of his allergies: “Ragweed season, ya know.” I pulled him onto my lap like I used to when he was a baby and let him cry. I shooed Sophia away so he wouldn’t be embarrassed.

One night, at about two a.m. when we all should’ve been sleeping, Darwin sat up and in a clear voice said, “I saw Ba.”

The darkened room was il

luminated by the plug-in nightlight. It cast shadows on my posters of Duran Duran and Sophia’s numerous Madonnas.

“What d’ya mean, dummy?” Sophia hissed. She had a low tolerance for nonsense.

“I mean, Ba woke me up. He was standing right there,” Darwin pointed to the foot of his mattress. “He said he just wanted to say hi, and to tell you guys not to worry because he’s gonna take care of everything. He has big plans for us.”

“Shut up. It was just a dream,” Sophia still sounded annoyed, but her tone had softened.

“You shut up, stoopido. It was real. I even heard you and Mir snoring, so I knew I was awake. He said not to wake you guys, that you wouldn’t believe it. And he’s right. You don’t believe anything I say.” Darwin sulked in the darkness. I heard the familiar clip of his nail against the side of his nose, and sure enough, even through the darkness, I could see him flick a piece of dried snot at Sophia.

“What else did he say, Dar?” I asked gently. I reached my hand down towards him and he took it.

“Nothing. He just said we were gonna be okay. Things are going to change, and that it’s all part of the plan. Then he played Super Mario Brothers with me, and ate some of the tuna casserole that Mrs. Norway brought. He said it had too much Velveeta.”

Sophia snorted, but I didn’t.

“Do you think Ma’s ever gonna come out?” Darwin said while gazing at Madonna. Darwin still needed Ma in those pragmatic childish ways. But I knew he would be okay. My worries were actually more for Sophia. She and Ma had always had a much more difficult relationship, locking horns over what Sophia wore, the friends she chose, and the music she listened to, but it was probably because they were so similar. When they were good, they were like the best kind of sisters. I remembered when Ma had taught Sophia how to sew, and how they’d spent so many afternoons bent over patterns spread over the kitchen table, their hair touching.

“Yah, Dar. I think she’s gonna come out soon,” I replied, without much conviction. Ma worked in extremes, which made her hard to predict. Sometimes, she was all organization and efficiency, whirling through cooking, shovelling the neighbours’ walks, and hosting her mah jong group, and she’d keep all this up until she and her nerves crashed, like a wind-up doll that slowed down to a standstill. When that happened, she would stay in her room for days until Ba bundled her up in her robe and carried her to the car. They always did this late at night, after he was sure the neighbours were inside. He would return a couple of hours later or even the next morning, acting edgy, his usually neat hair looking like his fingers had raked through it over and over again. He would smell a bit sour, and his bloodshot eyes would droop.

We all learned the routine after going through it a dozen times. Ma would go away to a hospital — “Not a real hospital,” Ba assured us. “A place to rest. That’s all”— and come home after one week. She would return with dark circles under her eyes and thin as a grasshopper, but she would be better. Darwin, Sophia, and I would then hold our collective breath until she joined us in the world of the living. Until then, Ba tried everything to make life fun by cooking Hamburger Helper and letting us eat Twinkies. Darwin had been too young to be truly troubled by it, and I had been old enough to play along and pretend everything was normal, but Sophia scratched and scratched at her arms until they bled, and for a change, said little.

In another week, usually, Ma would be back at the mah jong table as if nothing had happened, making the Pope proud with her good deeds, and clipping the National Enquirer to show us the latest miracles. She had been especially impressed with the image of Jesus found on a piece of grilled toast in Texas. Ma had always loved her miracles. And Ba, for all their issues, truly loved Ma. It seemed that all he had ever wanted was to make her happy. Back in Hong Kong, Ba had liked to put a Beatles album on the turntable and dance around the living room, swooping us up to the lyrics, “she loves you, yeah yeah yeah,” Ma’s song. Eventually Ma would relax and shake her hips too. Clearly she’d been fun at some point before Ka-La-Dai; there was a photo in the album of her as a teenager wearing knee socks with the faces of Paul, Ringo, John, and George all over them. We kids used to fall into paroxysms of laughter whenever we looked at it. Now, thinking about it just made me feel sad.

With Ba gone, Ma was in charge. This thought made me feel like I was falling from a tall building. Every so often, I would take a large gulp of air, realizing I hadn’t breathed in a while. She might have been in charge, but she wasn’t there, and this time, neither was Ba. I was the eldest, so as any book or movie would tell you, I was supposed to step up and take care of things. But I was supposed to be going off to university; that was my right. Now, I had a snotty brother and a snide sister and an absentee mother and a dead father and no idea what to do next. I resented that Ba hadn’t visited me. He was probably still mad I hadn’t backed him up on Disney World. Fuck Disney World, I wanted to yell. That’s the American dream, Ba. This is Canada, which, by the way, is not all it’s cracked up to be! I wanted to scream all this at him, to kick down doors, to let my hair loose and fly over the night sky, one leg outstretched as I arced over the houses, the mowed lawns, the stupid sedans, and across an empty moon. But instead I stayed quiet and very still.

Chapter 5 ~

Bao was just a maid, a ghost of a girl who left clean floors and hot tea. No one saw her, but they were pleased there was always feast at the table.

TWO DAYS AFTER his reported sighting of Ba, Darwin ran out of the room while we were eating microwave pizza, picked up the violin from the corner of his bedroom and, with sauce still around his mouth, began to play. The torrent of stirring, striking music that flew with such fierce artistry from my brother’s little hands was so lucid, so beautiful, it was almost horrifying. This, from a kid who normally rendered awful squeaks from the violin and hated his lessons.

We ran into the room, grabbing at napkins on the way. “What the hell was that?” yelled Sophia.

Darwin paused, his bow firm in the air above the strings, and with his wrist, pushed back the curtain of jet-black hair from his tiny face. We were all frozen. “That’s not even your violin,” squeaked Sophia. “It’s the school’s…” she paused. “But you normally suck at this.” I could tell she was at a loss. She often spewed random facts when she didn’t know what else to say.

“Darwin, where did you—” I started to ask before pausing at a shuffling in the hall. It was Ma. On one side of her head, the pillow had flattened her greasy hair so that it stood straight up. She was wearing Ba’s pajamas and the extra length in the leg pooled on the floor. She looked sad and sweet, like a child, not nearly as bad as I had imagined she might.

Ma stood in the doorway and watched Darwin play, her eyes regaining focus. Sophia was still in the far corner of his bedroom, looking down at the instrument as he played. “So, what the hell was that?” Sophia repeated.

“Dunno,” said Darwin shrugging. “I think I might have heard it on CBC or something.” He went to put his violin back into its case when he looked up. “Ma!” he jumped.

Ma went to Darwin in fast steps. She held his face in her hands, looking down at him. Then, she hugged him to her body. I could tell that Darwin was uncomfortable by the way his eyes bugged out because Ma was squeezing him in an iron grip. “Tsai tsai,” Ma said, “Ho teng, ho teng.” Little boy. Sounds good, sounds good. Then she looked disdainfully at the sauce on his face, released him and went to the kitchen to cook us a proper lunch. I was stunned on both accounts: first, by Darwin’s freakish music, and then by Ma actually getting out of bed. Maybe things would be okay.

That evening, while Ma cleaned the house far more effectively than we had the whole time she was in bed, Darwin demanded to be taken to a piano.

“Dar, cool it, okay? Ma just came out. We’ll find one tomorrow,” I told him, nervously eyeing Ma as she plugged in the vacuum. She had even taken a shower and was looking almost like her old self, except that she w

as very thin.

“Mir, I’ve got to. Please, Mir! I need to…” Darwin implored, his hands flapping up and down as the vacuum started its loud whir that drowned out the rest of his voice.

He tried again, screaming this time, “Take me to a piano, damn it!”

The roar of the vacuum suddenly ceased. “What’s that? What did you say, Darwin? Did you say a bad word?” Ma asked him, a hand cupped to her ear.

He ran to stand in front of her. “Ma, I need a piano. Right now. Please, Ma!” He bounced up and down, reminding me of when he was little and needed to pee.

Before he whined anymore, Ma had her apron untied. “Okay, okay Darwin, let’s go.”

Ma called a taxi and made the driver go super fast. Sophia, Darwin and Ma slid back and forth on the vinyl seat in the back while I gripped the handle bar in the front passenger seat for dear life and peeked every so often back at Ma.

“Hey, Ma, we don’t have to go right now.”

“No, no. Darwin needs a piano. Something is happening to him. We have to listen!” The cab made a sharp right turn into the driveway of the mall, the back of the car slamming and springing back from hitting the sloped pavement.

In the mall, we took Darwin directly to the music store. He walked along a row of pianos, running a hand softly over each one. At one black Yamaha upright, he sat down and his tiny fingers released a flurry of notes even as he struggled to reach the pedals with his feet. After he finished, we were once again stunned into speechlessness. A customer who had stopped in front of Darwin to stare, whispered reverentially, “That’s Chopin’s Fantaisie-Impromptu.” Sophia’s mouth hung open. He got up from the piano and moved toward the percussion instruments. We followed him like zombies. He picked up random instruments and immediately launched into pieces of complicated music. Stringed, percussive, brass, wood — it didn’t matter. He knew them all. Passersby in the mall, drawn in by the music, gathered around him in the store.

The Wondrous Woo

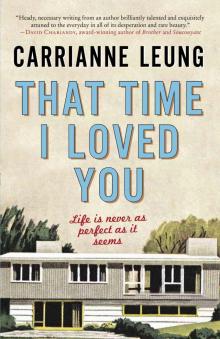

The Wondrous Woo That Time I Loved You

That Time I Loved You