- Home

- Carrianne Leung

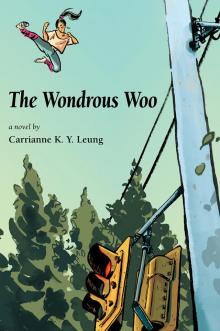

The Wondrous Woo Page 12

The Wondrous Woo Read online

Page 12

I walked by the Golden Harvest Theatre, the cinema where Ba and I had spent so many Sunday afternoons. A man was sitting on the steps, smoke trailing lazily up from a cigarette he had in his ungloved hands. I wondered, as I widened my berth to walk by, whether he was cold, maybe homeless.

“Yo. Got a cigarette, lang lui?” Lang lui, pretty girl. That was the last thing I felt like.

“Nope. Sorry,” I answered, quickening my steps.

“Ya want one?” He held his cigarette up toward me.

I could not help it. I laughed out loud and looked at him. It had not been a normal night, and my loneliness wanted the romance of smoke wafting up from my fingers. Suddenly, I had wanted nothing more than to be the kind of person who talked to strangers and accepted their cigarettes. To be that free.

I backed up, approached him, and saw a young face. He could have even been my age, and was kind of cute. His eyes drooped down toward the corners like moons as he smiled. He had a long face with slender lips, the mouth of a woman.

“I’m Mouse,” he said as he offered his open pack of cigarettes. I slid a cigarette out along with a lighter. I lit the cigarette, inhaling deeply to draw in the fire. It made me cough, and soon I was doubled-up, hacking into my hands. Mouse stood and patted my back the way my parents used to when I had choked on something.

“Thanks,” I said, straightening up, embarrassed. I handed him back his cigarette and started to walk away, feeling ridiculous talking to a stranger, letting him touch me, and then looking like an idiot.

“You’re welcome!” he called after me.

The cigarette had given me a headache. I wondered how I was ever able to match Jerry smoke for smoke when we were together. I had done a lot of weird things to fit in with Jerry and the North Bay crowd. But, of course, I never quite fit in, and that was easy for me to see now. Still, being dumped smarted, like the aftermath of a slap.

I wondered what Jerry was doing that very moment that I found myself walking north on Spadina Avenue. Was he having sex with the old/new girlfriend? Was he biting the nape of her neck the way he used to bite mine? Such thoughts made me feel sick and heavy but I could not stop them rushing at me. I wanted to go home, but that home sat empty in Scarborough. I had no idea if the lights still worked. Whether it had heat. Numb from the cold, I headed back to the only place I had left to go, Ma’s condo.

The next afternoon, William came by to see Ma. He had told the nurses that he was Ma’s fiancé. It could have been true for all I knew, and I felt outraged and helpless. He sat on the other side of her and held her hand. I hated that he didn’t mind sitting there, holding my mother’s hand, right in front of me, invading my space, my time with her. He did things he should have done in private: whisper in her ear, caress her hand. I didn’t get it; Ma used to bat Ba away whenever he tried to be affectionate. Any show of love made her jump like she had touched a snake. “Aiya, Mm ho la!” Enough! she used to screech. I wanted to whip William’s hand away and shout too. But instead I sat there, stupid, like I was the third wheel in my own life.

“Miramar, what happened?” he asked, looking up at me. “I don’t understand.”

I thought of the million answers I could give him. What happened? Search me, pal. “Ma has … a condition. I don’t know if she ever talked about it,” I began. He shook his head.

“Maybe you can ask her when she’s better,” I said. This was the only answer I would give to William K.C. Koo. He was not my family, and Ma would have to decide whether he was hers.

Ma woke up later that afternoon. William had long gone back to work. I had a paper due and an exam the following week, but I was reading an old People magazine I had stolen out of the waiting room. School seemed like another world, another lifetime. Besides, this was the 25 Most Intriguing People of 1987 issue. An education in its own right, I reasoned.

I was deep in an article about Cher when Ma’s eyes fluttered open. “Miramar?”

“Ma?” I dropped the magazine.

“Where am I? What’s happening?” She rubbed her head. “Wah. Such a headache.” I saw her eyes travel over the sterile room, the light blue sheets covering her body, the IV hooked into her arm, but she looked confused like nothing was registering.

“You’re okay, Ma. We’re in the hospital. You just had a big sleep.”

“It happened again,” she turned her head away and sighed. She was silent for a long time, staring at the wall. “You know Ba was the one who wanted to come to Canada,” she said so quietly I barely heard her. “He was the one who said it would be a good life for all of you. A big house. A yard. You would all grow up healthy and smart.” I pulled my chair closer, so I would not miss a word.

“He went on and on. For years. You were just born when he started. Then Sophia. Finally, I said, okay. Why not? He knew best.” She sighed again.

“He was always crazy for English. Wanted to speak to you both in English right away so you would learn. Ka-La-Dai. Always going on about Ka-La-Dai. Open spaces, good air, lots of opportunities there, he said. So, we came.” I had never heard my Ma talk like this before. She never referred to the past, back in Hong Kong. I used to beg her to tell me stories of when we were there, but she would never do it.

“We came in February. Darwin was still in my arms. We stepped outside of the airport, and I screamed from the cold. Aiya! It was a terrifying cold. I hugged all of you to me, so you didn’t freeze,” she grimaced. “Your Ba convinced me he loved it. He loved everything about Ka-La-Dai. We used to live in that dirty apartment, remember? No, you were too young to remember. The pigeons used to make nests on the balcony. So filthy. Poo everywhere. Ba convinced me he loved the pigeons too. Everyone should have a home, he said. He even took some of the eggs out of the nest and tried to hatch them in the oven for you girls. Your crazy Ba.”

I did not remember any of this, but could very well see my Ba doing this.

“And look what happened? I became the one who went chi seen. Crazy! Funny, ha?” She turned to me then. “I hated it here. I hated everything. I hated the snow, I hated the heat, I hated the people, I hated the house, I hated the sky. I went — what do you say in English — ‘cuckoo’!” She spat the words out.

“I wanted to go home. Back to my friends. Back to where people didn’t look at me like I was an animal. I wanted my old neighbourhood. I wanted to smell the harbour.” She was really scaring me, but I could not tear my eyes from her face, all twisted now in raw pain.

She was not trying to control her tears; they fell and fell. Her nose ran. I bent over and held her. I had never embraced my mother before, and she felt fragile as if I could break her if I hugged her too hard. She did not hug me back. Her arms stayed limp on the bed.

“I couldn’t ask Ba to leave. You were all happy here. He was right. You three children growing up, big and strong. Smart. Going to school. It was right to come. Ba was right. But then, why couldn’t I be happy?”

“I don’t know, Ma. I’m sorry. I didn’t know,” I murmured. I finally let her go. She sank back into the pillow and closed her eyes. I sat back down and kicked at the magazine on the floor.

She didn’t say any more to me that day. Later that night, I phoned Sophia and Darwin to tell them that she had woken up, and had even eaten a little.

There was relief in Sophia’s voice. “It was my fault, wasn’t it?” She sounded so tiny.

“Oh, Sophia,” I exhaled loudly. I wasn’t in the mood to console my sister. I was exhausted. Would it have hurt her to ask how I was? “It wasn’t your fault. Ma’s been like this for a while, you know.”

“But I know I piss her off. I just get so mad her. Sometimes, I feel like she just doesn’t like me. And then we fight…” she paused. “Maybe I should have been nicer to William.”

“Sophia, you can tell her this yourself. As for not liking you, you don’t seriously believe that. You’re her daughter. She loves you. Y

ou may even be her favourite.”

“Tell her? Mir, I can hardly carry on a conversation with her half the time these days. All of our phone calls end up with one of us hanging up. Everything I do is wrong. If I really told her what’s going on with me, she would flip. Maybe get way worse than she already is.”

“Well, you can’t blame yourself. Ma’s problems are … chemical. That’s what the doctor said. Just try to be easier on her. She’s had a rough time. She’s the only parent we’ve got,” I said this last sentence as an afterthought. Once said, the gravity of it weighed on me.

I thought about telling her what Ma had told me, but knew Sophia didn’t have the fortitude to handle such a burden. I thought about the scratches on her arms and wondered if she was doing it even now on the phone with me. For all her tough act, I knew that when it came to Ma, Sophia was just a little girl who needed to be reassured that everything was going to be all right. I wished I could do that for her now, the way Ba had done it for all of us.

While I was sure Darwin was relieved too, he was back to his one-word sentences.

“How’s your face?” I asked.

“Good.”

“Healing okay?”

“Yup.”

Okay, then. One mother in the pysch ward, heavily sedated, check. One sister blaming herself for her mother’s psychotic episode, check. One brother who preferred to grunt monosyllabic words rather than have a real conversation about any of this, check. One father dead, check. Family falling into pieces before my eyes, check. I wondered where that left me.

It was serious what Ma had said, and I did not have the energy to think about it. It meant that during our whole lives together, she had been trying to be happy, but failing, and lying to us all.

When I arrived at the hospital in the morning, William was already there. Ma was sitting up in bed, dressed in a jogging suit. She smiled widely at me when I entered. Dr. Pang was also there, all business with her lab coat and files. Confused, I looked from Ma to William to Dr. Pang, wondering why I felt like I was interrupting something.

“There you are!” William announced like I was the guest.

“Nui, nui. I can go home!” Ma pronounced this like she had won a trip to Hawaii.

“Yes, she can. Make sure she is good with taking her medication and coming in for her appointments so I can monitor how it’s working,” Dr. Pang spoke to me like Ma was my kid.

“Oh, don’t worry, Doctor. I will be making sure she does everything she is supposed to,” William replied. Who was talking to him? Dr. Pang acquiesced to William and for the first time, I saw her smile. I guess William did have some people skills, or Dr. Pang finally found someone she felt she could trust with Ma’s care. I believed the latter. Could not blame her, really. Every time she talked to me about Ma’s condition, I just stared at her with my mouth open.

She bent down to Ma and said, “Be good.” Ma gave Dr. Pang her best Catholic smile.

“Miramar, I have it all taken care of. Your Ma will be staying with me at my house until she feels better. You don’t have to worry about a thing. Go back to Ottawa to your classes. We’ll be in touch to tell you how she is,” William stated. Ma gave him the same congenial smile.

“Ma,” I began. Her serene smile was still there. “Is that okay with you?”

“Yes, yes. All okay,” she said softly. William was holding her hand again, and she was letting him. They were staring at each other, and it seemed right for me to leave.

I wanted to slap William’s smug face and Ma’s sedative-laced grin, but instead, I walked away. I crossed the long hallway full of fluorescent lights. They were so bright, they burned into me. I was sweating under my scarf. I pressed the elevator button, once and then I banged it over and over. When the elevator finally came, I stepped in and leaned against the wall. I went back to the condo, packed my bags, and caught the first bus to Ottawa. Ma had chosen. What could I offer her? Would I leave school and move into her condo? Would I be able to talk her back from her ledges? Yes. I would have done all of these things and more if she had given me the opportunity. But perhaps William could give her what none of us could, not me, not Sophia, nor Darwin, not even Ba.

The thought of Ba felt like a stab in my heart. Did Ma think so little of his memory that she was ready to fly into William’s arms? Ba had given everything to us, even his life just so he could get home to us a little earlier. I could accept Ma betraying me or even Darwin and Sophia, but I couldn’t accept this betrayal to Ba.

What Ma had told me played over and over in my head. The Ma I knew who could not stop being useful to everyone, the Ma who played mah jong passionately with her friends, the Ma my Ba adored. All of it was false. She had been unhappy the whole time, having us believe that she loved us. Meanwhile, she lived her life with a million regrets. She regretted everything, and the only way out, the only way to escape us, was to go nuts. She thought we were so awful? Then, to the hell with her.

I knew then what was between the nuthouse and the grave — nowhere. I was nowhere.

Chapter 21 ~

Crawling to the edge of the lake, Wai-ling was desperately thirsty. Her armour was in pieces, and she bled from where the arrow was stuck in her leg. Under the night sky, she scooped water into her mouth frantically, crying as she drank. After, she yanked the arrow from her limb and laid on her back. She would either die here or be born anew. Either way, she was conspiring with the stars.

WHEN I GOT BACK to Ottawa, I sorted through my things. I couldn’t be with Ma, but I realized on the bus that I couldn’t be in Ottawa anymore either. I found a few photos of Jerry tucked into a mostly unused journal. There were no photos of us together. It felt so long enough ago that I could almost believe it never happened. I threw the pictures away, wondering if we had ever existed as a couple at all. I wasn’t angry with Jerry anymore, just numb.

I gathered the “Dormant” client files and shoved them in my suitcase then poured my kung fu videos on top. My makeup, including Revlon’s “Spring Blush,” went into the garbage bag. It took me less than fifteen minutes to pack all my worldly belongings into the same suitcases I had brought to Ottawa. By the time I was finished, I had less than I had originally brought with me a year and a half ago when I moved there.

I went to the bank and closed my account. I had over five thousand dollars. I asked the teller for an envelope and stuck it into my jacket pocket. I thought about phoning Kathleen to say goodbye. She had been nice to me. She had tried, in her own way, to watch out for me. I wanted to thank her, but I couldn’t decide how to begin. Maybe I would write her a letter, one day, when I could actually tell her something worth saying.

I boarded another Greyhound. This time, I was heading back in the direction whence I came. This time, however, instead of being a young, promising university student, I was going back as a slightly older, hardly wiser, university drop-out.

Chapter 22 ~

Lai Wing had to hide from her family who was forcing her into an arranged marriage she did not want. Her would-be groom was an old, ugly, rich guy with a hairy mole on his chin. Lai Wing had to find a way to carve out her own life, cut loose from family and funds. What her parents, her shunned groom, or anyone from the village did not account for was her industriousness, tenacity and deadly kung fu prowess. With a ninja-like cloak, she became a hired assassin, avenging people for extortion from greedy landlords. Lai Wing was revered at the end of it all. (In the background: Aretha Franklin singing “R-E-S-P-E-C-T.”)

BACK IN TORONTO, I checked into a cheap hotel on King Street and started to look at apartments for rent. I saw a bunch, including a flat in an old rambling house in Chinatown. It had peeling red paint on the brick, and it leaned slightly to the left. It stood side by side other houses that also looked to be in various stages of dilapidation. An ancient Italian woman lived downstairs and was officially my landlord although it was her son who rented the upstairs apart

ment to me.

“She don’t speak English.” He had waved in his mother’s direction dismissively when he gave me the tour.

Downstairs, I looked in the direction of the open front door and saw the wizened woman sitting in a chair in the darkened hallway. She peeked out, her head extending on her neck like a turtle’s, and followed me with her eyes.

As I toured the apartment, the son gave me the story of the house. He had grown up there. His parents had emigrated from Italy in the 1940s. His dad was a construction worker.

I was charmed by the place. The ceilings were more than ten feet high. The living room had two large windows that almost spanned the entire wall and looked out into the street. This room would make a good kung fu space.

There was a large kitchen, big enough for a table, an even larger bedroom that walked out onto a fire escape, and a tiny bathroom with a shower stall. Different layers of wallpaper showed through various tears, but the rooms were filled with light. When I opened all the windows, the most delicious crosswind moved through the house. I didn’t need to think. “I’ll take it,” I said, and began pulling hundreds out of my wallet.

The man paused, looked at me, and laughed, a hearty, warm laugh. “I like it when a woman knows what she likes,” he said, then smiled. “It’s a happy house. You’ll see.”

He left me alone to enjoy my new home for a minute. As I walked through my empty apartment, I was surprised by an excitement that came over me. A year and a half ago, I was a suburban teenager thrilled about launching my adult life — university, employment, and maybe, deep in the future, marriage and a family of my own. All those markers stretched ahead of me, a map with clearly marked signs and signals. Was life so random that one careless move while crossing the road could change the course of everything? Could one second shift the history of the world and everything in it? I only knew that this empty apartment, this moment, this Miramar was not supposed to be part of the trip. While it didn’t feel like a step backwards, it was definitely a step outside. No more maps; I was on a detour.

The Wondrous Woo

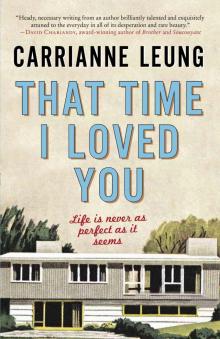

The Wondrous Woo That Time I Loved You

That Time I Loved You